The incredible exploits of Sunderland First World War hero George Maling VC, who helped 300 wounded men while under heavy fire

and live on Freeview channel 276

Anyone who accepts the definition will therefore agree that it’s an overused word.

When the word is applied, as it routinely is, to people in the spheres of sports, entertainment or even business, it demeans the achievements of those who are truly heroic – such as Sunderland soldier George Maling, who remains the city’s only Victoria Cross recipient.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat Lieutenant Maling managed in September 1915 in France sounds like something from one of Hollywood’s less plausible efforts. But everything you are about to read is completely true.

First some background

George Allan (sometimes spelt Allen) Maling was born in Bishopwearmouth on October 6, 1888. The Malings were well-to-do. The family was renowned for Maling Pottery, which made them rich. On his mother’s side George was related to another Sunderland military star, General Havelock.

He was educated at Uppingham School in Rutland, which today charges boarders £14,000 per term. At Oxford he gained an honours degree in natural sciences, before continuing studies at St Thomas’s Hospital in London, qualifying as a surgeon and physician in 1914.

As was the case with millions of others, a cosy (in his case, privileged) life was spectacularly and abruptly interrupted by World War One. He was commissioned as an officer into the Royal Artillery Medical Corp in January 1915, joining the 12th Battalion Rifle Brigade as medical officer.

By July 1915 he was in northern France. In the thick of it.

His finest hour

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Battle of Loos took place from September 25 to October 8, 1915 on the Western Front. Combined British and German casualties were around 85,000 men.

It is indicative of the horrific scale of the war that the battle is far less famous than the likes of Ypres and the Somme. The Loos Memorial in Pas-de-Calais commemorates over 20,000 soldiers of Britain and the Commonwealth who fell in the battle and have no known grave.

However, Maling’s heroism was only indirectly to do with Loos. Early on September 25 the 12th Battalion Rifle Brigade was part of an attack on the enemy line at Piètre. This was to divert German resources from Loos.

The action was about 60 miles inland from Calais and 25 miles from the Belgian border. The British used gas – disastrously. The wind carried it back on themselves.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe 26 year-old soldier and surgeon was about to cover himself in glory; although it was not glory he was seeking. His VC citation referred to his “most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty during the heavy fighting near Fauquissart on 25th September, 1915.”

It continues: “Lieutenant Maling worked incessantly with untiring energy from 6.15am on the 25th till 8am on the 26th, collecting and treating in the open under heavy shell fire more than 300 men.

“At about 11am on the 25th he was flung down and temporarily stunned by the bursting of a large high-explosive shell, which wounded his only assistant and killed several of his patients.

“A second shell soon covered him and his instruments with debris, but his high courage and zeal never failed him and he continued his gallant work single-handed.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt wasn’t quite single-handed. The assistant mentioned in the citation was a brave, yet unnamed orderly. They moved calmly from casualty to casualty on no-man’s-land, occasionally shielding their patients from bombardment with their own bodies.

Both men were blown backwards by an explosion. The surgeon was somehow uninjured, but the orderly lay wounded amid a pile of bodies and was treated by Maling, who not only treated the stricken but also gamely attempted to raise their spirits.

The phrase “putting in a shift” has rarely been more applicable. Adrenaline must have kept him going for so long and for this he was awarded the highest possible military honour.

The British captured the German front and second lines. But a German counter-attack soon forced them to withdraw.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe exchange was a stalemate. The action it was supposed to divert enemy attention from, the Battle of Loos, was ultimately won by the Germans. None of which detracts from the incredible bravery of a Sunderland surgeon and soldier.

After the VC

Lieutenant Maling was promoted to captain in 1916. After a short stint at the Military Hospital in Grantham, Lincolnshire he returned to France for two more years of duty.

On March 17, 1917 the Sunderland Echo reported that he had married Miss Daisy Mabel Wolmer, a nurse from Winnipeg, Manitoba.

George Maling’s obituary wrongly stated that he had one son. He and Daisy had four children, the eldest of whom, John Allan Maling (1920-2012), became a doctor and won the Military Cross for his actions in Algeria in 1942.

The end and the legacy

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeorge Maling survived World War One, but was not to be blessed with a long life. After the war, he became resident medical officer at the Victoria Hospital for Children at Chelsea. He then set up a practice in London and also became a surgeon at St. John's Hospital, Lewisham.

He died from pleurisy on July 9, 1929 aged just 40 and is buried at Chislehurst Cemetery in Kent.

Some Wearsiders think their hero is buried in Bishopwearmouth Cemetery. This is not correct, although there is an inscription in his honour at the Maling family grave there. Daisy died in 1973.

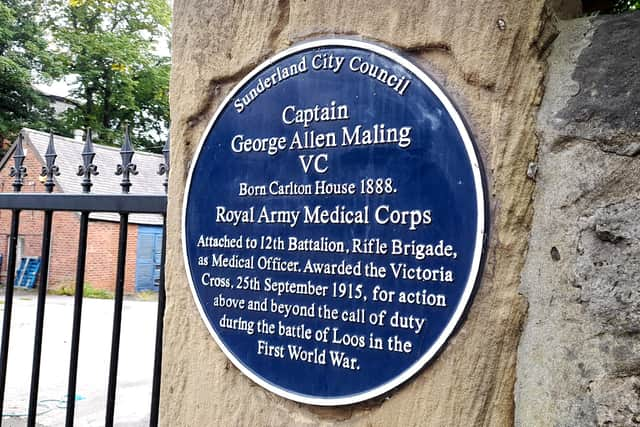

In 2015, a century after his finest hour, a blue plaque in his honour was put up at Carlton House, his former Sunderland home on Mowbray Road. His grandson, Dr David Maling, attended the unveiling.

At the cenotaph on Burdon Road, a specially commissioned commemorative paving stone was laid.

His VC is kept in the Museum of Army Medical Services in Aldershot.